Over the two decades before COVID-19 struck in 2020, Cambodia blossomed economically. Having reached lower middle-income status in 2015, it set its signs on attaining upper middle-income status by 2030. Thanks to garment exports and tourism, Cambodia’s economy grew at an average annual rate of 7.7 percent between 1998 and 2019, making it one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

Post-pandemic, Cambodia’s economic recovery has gained momentum, but remains uneven. Traditional growth drivers, especially manufacturing and agricultural commodities exports, have fully recovered. However, while travel and tourism have improved, the sector remains well below pre-COVID-19 levels. The pick-up in tourism is due to both rising domestic activity and increasing international arrivals. The construction and real estate sector, another important pre-pandemic growth driver, remains sluggish. The economy is projected to grow 4.8 percent in 2022, upwardly revised from a forecast of 4.5 percent in April, underpinned by merchandise exports and domestic economic activity. Foreign direct investment (FDI), while diversified, remains affected by China’s zero COVID-19 policy.

Cambodia’s export-oriented manufacturing sector is expected to face headwinds from a less favorable external environment reshaped by slowdowns in the United States and China. In addition, energy and food price hikes due to the war in Ukraine are expected to weigh on household budgets and slow poverty reduction. To blunt the impact of high inflation on vulnerable households’ welfare, the government is considering additional fiscal interventions.

Over the medium term, the economy is expected to grow around 6 percent annually as the new investment law and free trade agreements help boost investment and trade.

Cambodia has recently redefined the poverty line, using the most recent Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey for 2019/20. The national poverty line is now 10,951 riels per person per day or the equivalent of $2.70 (at October 2022 exchange rates). Under the new poverty line, about 18 percent of the population is identified as poor. Poverty rates vary considerably by area. The poverty rate is the lowest in Phnom Penh (4.2 percent) and other urban areas (12.6 percent), and the highest in rural areas (22.8 percent).

Over the period 2009-2019/20, poverty rates declined by 1.6 percentage points a year, driven substantially by rising labor (especially wage) earnings. However, the COVID-19 pandemic led to increases in unemployment, poverty, and inequality. The scale-up of social assistance to poor and vulnerable households, launched in June 2020, has moderated income losses. The increase in the poverty rate in 2020 is projected to have been limited to an increase of 2.8 percentage points. Poverty nevertheless remains higher than pre-pandemic levels.

By contrast, a survey of households shows that employment has returned to pre-pandemic levels. The negative effect of the pandemic on non-farm family businesses has stabilized; however, low consumer demand remains the main driver of revenue losses. One-third of households continued reporting declines in income between April and May 2022. This suggests that the proportion of households negatively affected by COVID-19 is still higher than those received cash transfers from the government, which could lead to an increase in poverty.

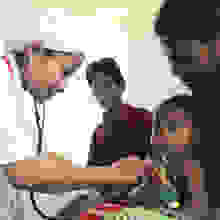

Cambodia has made considerable strides in improving health outcomes, early childhood development, and primary education in rural areas. Life expectancy at birth and maternal, under-five, and infant mortality rates have been improved significantly between 2000 and 2021. Despite this progress, human capital indicators lag other lower middle-income countries. In 2020, a child born in Cambodia would be expected to be only 49 percent as productive when grown as she or he could be if she or he enjoyed full quality education, good health, and proper nutrition during childhood. In the 2021-2022 academic year, net enrollment rates for primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary education (both public and private) reached 93 percent, 46.7 percent, and 28.6 percent, respectively.

Key reforms are needed for Cambodia to sustain pro-poor growth, foster competitiveness, sustainably manage natural resource wealth, and improve access to and quality of public services. Cambodia continues to have a serious infrastructure gap and would benefit from greater connectivity and investments in rural and urban infrastructure. Further diversification of the economy will require fostering entrepreneurship, expanding the use of technology, and building new skills to address emerging labor market needs. Accountable and responsive public institutions will also be critical. Boosting investments in human capital will be of utmost importance to achieve Cambodia’s ambitious goal of reaching middle-income status by 2030.

Last Updated: Oct 19, 2022